Madame’s eyes took on a faraway quality.

“I have knelt only twice in my life. Once for a queen…and once for a Nazi who held a gun to my head.”

~ ~ ~

“Alright. Enough seriousness. I promised you a story about the first time I drove an automobile.”

The tension broken, Jean stepped forward with her medical bag and knelt next to Madame’s wheelchair. She exchanged a relieved look with Ebony, then went to work on Madame’s leg. Ebony felt giddy as she plopped herself on the overstuffed pink couch, hugged a pillow, and folded her coltish legs under her derrière. “I’m ready.”

Madame grinned. Her entire face lifted, and her eyes took on an impish quality. “It was 1943. Stefan had been gone over a year, and my work was now overseen by another man named Michael, a tall, handsome, young American who gave me my code name.”

“You had a code name? That’s frickin’ cool!”

Madame pulled back a bit and tilted her head. “Excuse me?”

Ebony twisted her mouth in embarrassment. “I mean, it is kind of cool, don’t you think?”

Madame smirked. “I suppose it is…frickin’ cool.”

Ebony laughed out loud. “Yeah, it is! What was your code name?”

“Swallowtail.”

~ ~ ~ “

My version of happiness was shattered during the war when many of us were tested in unimaginable ways. I now truly understand what is important and what is not.”

Ebony leaned forward. Now this was some information she could put to good use. “So…what’s important?”

A cloud crossed Madame’s features. “I cannot answer that for you, my dear. What is important to me may not be important to you. You are on your own journey of discovery. I am a bold woman, but I am humble enough to realize I have no right to dictate importance. Young people today seek validation through others. But when you allow others to form your worth, you don’t do the hard work of determining what’s truly important to you. You’re cheating yourself out of integrity and losing the strength of having convictions to live by.”

Ebony twisted her mouth in thought. Although she’d been lectured to about qualities her generation lacked, no one had ever framed the argument in such a forthright, honest manner. When she sifted through Madame’s comments, she realized she didn’t want to be responsible for cheating herself out of anything. “I’ve never thought of it that way.”

“Just as true strength is quiet, grace and dignity are found within oneself. You will never find inner peace on a computer screen or by how many likes you get on a post; those are hollow and don’t stand up to even a small breeze. We have choices each day. Between right and wrong, kindness and cruelty, faith and faithlessness. It’s what we do with our ability to choose that defines who we are, what we stand for. So here is my question for you, my dear Ebony. What do you stand for?”

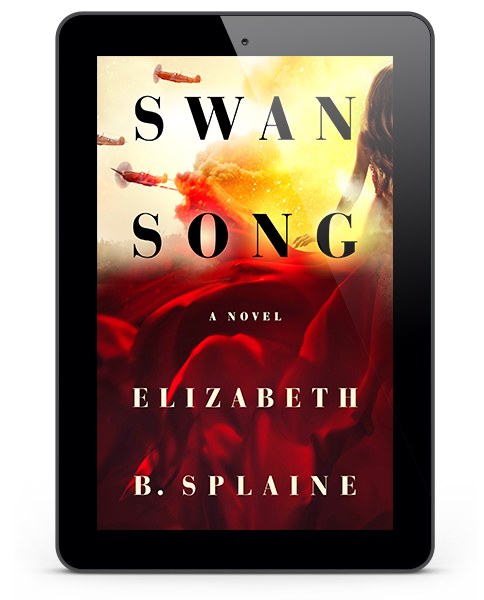

Swan Song

Prologue

Hitler was a monster.

Except he wasn’t.

He was a narcissistic sociopath who convinced millions of people to join his cult.

In his early years, observers might have called him a simple man. Or a man who lived simply in a tiny apartment with as close to a friend as Adolf Hitler would ever have. Hitler met August Kubizek at the Linz opera after Hitler’s family moved to Linz following the death of his father. Like all of Hitler’s relationships, the friendship was largely one-sided. As Hitler vacillated between silence and raving diatribes about perceived wrongs, his roommate was doomed to listen and nod appropriately until Hitler finally exhausted himself. His friendship with Kubizek ended abruptly when the young man returned from the holidays to find that Hitler had moved out, leaving no trace. For reasons known only to Hitler’s troubled mind, he had decided to end the relationship as suddenly as it had begun.

Hitler’s relationships with women were no less muddled and one-sided. While living with Kubizek, he fell in love with a young woman named Stefanie whom he spotted on the street. Over a period of months, he loved her from afar and never approached her. Instead, he fantasized about their life together and imagined that he communicated with Stefanie through telepathy. According to Kubizek, Hitler truly believed that Stefanie understood his thoughts and shared his unspoken passion. He even discussed the idea of kidnapping her, until Kubizek astutely pointed out that he had no money to support her. The fact that kidnapping is legally and morally wrong never came into consideration.

Hitler’s “love” was all-consuming, volatile, twisted. To him, loving someone meant possessing her, smothering the person’s spirit and will until she became a part of him. If, for some reason, the supply of love was severed, the victim suffered greatly, having poured herself- heart, mind, and soul- into Hitler. Subjugation was an unspoken requirement when becoming involved with Hitler. In the process, the person lost her own identity, her sense of self. And when that has happened, what remains? A husk, a shell, with roiling emotions and a desperate sense of loss. Stefanie escaped by never actually engaging with the megalomaniac. Other women were not so fortunate. At least seven women committed suicide after being involved with Adolf Hitler.

But of the seven, only one adversely affected Hitler.

Hitler was forty years old when he became the legal guardian of his half-sister’s daughter, Angela “Geli” Raubal, who was twenty-three. They lived together in a well-appointed apartment in Munich, her bedroom located right next to his. According to all accounts, Hitler adored Geli, and she enjoyed being the object of his attention. He showered her with gifts and paid for voice lessons when she showed some interest in the craft. He preened with her on his arm and thundered when she showed any interest in spending time with other men.

The relationship had limits, however, as Geli showed no interest in marrying him, and he was unable (or unwilling) to force his will on her. Still, he yearned to possess her, to control her every move. Seeing himself as a talented artist, he painted lewd pictures of her in the nude which were stolen in an effort to blackmail him (and reacquired through purchase from the blackmailer.) There are stories that he slashed her with a bullhide whip he often carried. But she remained by his side, like so many abused partners. She stayed until she could stand it no more. On the night of September 18, 1931, following yet another screaming match, Geli shot herself in the heart with one of Hitler’s Walther revolvers. Hitler was out of town. Geli’s body was discovered the following morning by the housekeeper, Annie Winter.

Next to the passing of his mother, whose picture he carried with him until his death, the suicide of Geli had the most dramatic effect on Hitler’s psyche. He ordered the suicide covered up, and, for the next two weeks he barely ate and rarely slept. According to confidants, he had to be physically restrained from committing suicide. In Hitler’s twisted mind, the death of Geli elevated her to a saint. Her bedroom became a shrine in which fresh flowers were placed each day to honor her memory. A full-length painting of Geli hung in Hitler’s alpine home near Berchtesgaden, commonly known as the Berghof. Underneath the painting always sat another bowl of fresh flowers. Hitler carried Geli’s picture next to his mother’s until his own death (by the same pistol Geli had used) in 1945. As his memory reinvented the young woman, her suicide became regal, an honorable, heroic choice to which he would refer again and again over the ensuing years.

There were several events in Hitler’s life that drove him closer and closer to the insane, autocratic tyrant he eventually became. But the guilt he felt at Geli’s suicide was the trigger that fully unleashed his complete lack of morality and conscience. As Robert Payne so aptly describes Hitler’s mental deterioration in The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler, “She was of his blood and flesh, almost a daughter and almost a wife, closer to him than anyone else in the world. To have caused her death was to have committed the ultimate crime; the guilt would remain, never to be washed away. Henceforth, he was free from all of the conventional ties of morality…He had gone beyond good and evil, and entered a strange landscape where…all the ordinary human values were reversed. Like Dostoyevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, he succumbed to ‘the dread spirit of death and destruction.’”

It is important that you, dear reader, understand Hitler’s state of mind as he makes the acquaintance of a beautiful young opera singer named Ursula Becker. In this story, he has been following her career from afar, much as he followed (and courted) Stefanie only in his mind. It has been several years since the death of his beloved niece when he finally meets Ursula Becker, who so closely resembles Geli that Hitler cannot help but be drawn to her. He yearns to possess Ursula, to consume her. But her will is strong and her personality rebellious. As she continues to defy him, his broken mind conflates the two women and, over time, the truculent Ursula becomes Geli. Hitler is left with two choices: once again cause the death of someone he cherishes or allow her to live and openly defy him. The personal decisions he makes, as seen through Ursula’s eyes, reflect the turmoil he continues to create throughout the world.

This is not a novel about Adolf Hitler, who died like a coward in an underground bunker instead of facing the atrocities for which he would have been held accountable. This is a story that represents the victims, a story about one woman’s struggle to survive against overwhelming odds as the object of a crazy person’s possessive passion. This is a love story that spans continents and time, war and cruelty. This is a story of the worst and the best that human nature has to offer, a tale of the resilience of the human spirit, of the Light against interminable darkness. And we all know that, in the end, despite the unthinkable atrocities that were waged on the innocent, the Light overcame the darkness.

Respectfully Yours,

Elizabeth B. Splaine - February 2021

SWAN SONG

Without warning his petulant demeanor changed dramatically. Singling out Ursula, his furious eyes burned as he repeated, “You did this. You did this.” He lunged forward and grabbed her wrist, forced her to stand, then dragged her out of the room, down the stairs and out into the snowy street. Ursula remained silent and ran to keep up with his long strides as visions of being shot or hanged ran rampant through her fertile mind. She knew better than to ask where he was taking her, and she steeled herself for what was to come.

Each time she stumbled he would drag her until she managed to stand again. By the time they reached a building three blocks away from Dresden, she was out of breath and struggling to see out of her swollen eye. Seidl slowed and walked her toward the Eger River. As they neared the edge of the bridge that crossed the river, Seidl stopped, stepped behind her and grabbed her shoulders. This is the end, she thought. He’s going to shoot me and throw me in the river. She closed her eyes and pictured Willy and Otto, allowing the wonderful images to wash over her like the water rushing below her feet. Her trembling body calmed as she spoke to Otto in her mind, silently saying goodbye. Willy whispered sweetness in her ear, reminding her who she is, and urging her to maintain her dignity and composure.

After several moments of silence, however, Ursula realized that Seidl hadn’t drawn his weapon. She opened her eyes and found that she was facing a building on the other side of the bridge. The Little Fortress. He’s going to imprison me, she realized. Like Herr Abendroth, I am to be jailed. But I will not die today. “Resist. Survive,” Willy whispered in her ear. A euphoric relief shuddered through her, and she sent a silent prayer upwards.

Seidl gripped her shoulders. “Do you see that building, Fräulein?”

Before she could answer, he shook her so hard that she was concerned her neck might break. His lips brushed her ear. “It’s as if you want to go there. Do you?”

Afraid to respond, Ursula remained mute.

He whipped her around to face him. “Do you?” he screamed in her face.

Ursula cringed and whispered, “No.”

“Then stop defying me! This will be your last warning!”

He shoved her away from him and raked his fingers through his hair, upending his cap, which fell to the snowy earth. “I don’t understand this hold you have on me!” He walked in circles as puffy, white snowflakes settled on his dark hair. After several moments he retrieved his cap, brushed it off, and replaced it on his head. Abruptly he turned to her and looked suddenly sad. “You came to me with special instructions.”

What does that mean? she wondered.

“I shouldn’t tell you that, lest it embolden you, but I can’t help myself. I had heard that you were a siren, but you are not. You are so much more than that. Even now…”

I do read, although far less than I used to. Usually a book I’m reading is affiliated in some way with what I’m writing. My favorite genre is historical fiction, and it drives me nuts when the author doesn’t tell the reader what’s real and what’s not. That’s why I included a note to the reader at the end of Swan Song. Right now I’m reading Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer by James L. Swanson. Even though I know how it ends, there’s so much detail I didn’t know about and his writing makes it exciting and heart breaking at the same time.

Having raised three boys while owning two great Danes and an English mastiff, I crave comfortable, controlled chaos. I need some sound. Having said that, I enjoy listening to classical music when I write. The soaring tones or soothing cadences carries me emotionally to different places I otherwise might not reach that, in turn, inform my writing.

If you could spend time with a character from your book whom would it be? And what would you do during that day?

I did spend time with Madame Celeste DeWit, or the person on whom the character was based. Although I knew her for many years, we became closer as we discovered how much we had in common. “Celeste” loved opera, so each time we were together I would sing with her or for her. Sometimes we sang together, me in Italian, her in native French. Those are special memories. I have pictures of me singing to her while she lay in what-was-to-become her deathbed.

She would let little tidbits of history sneak out while we spoke, like the time she sat in a meeting with President Eisenhower (she called him “whiny”), or the time she met Rommel in Paris. It turns out that some of the items I altered to maintain her anonymity were actually true. I didn’t know that when I wrote the book

But what linked us so completely was the fact that I saw her deceased husband’s ghost, clear as day, during one of her famous dinner parties. He smiled at me and faded away. Years later, when I told her about seeing him, she cupped my face and said, “But of course it was you who saw him. He loved opera.” It turns out the outfit he was wearing when I saw him (which I described for her) was his favorite. Where he was sitting and the manner in which he was sitting, also clear as day to me, were critical to my description, solidifying her (and my) belief that I’d seen him. Although I’d never met her husband, as he had died prior to my meeting her, he seemed at peace and was very much still in her life.

Gorgeous cover. Looks great. Sounds like a good book.

ReplyDelete