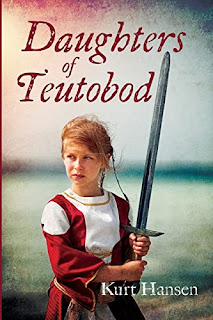

Daughters of Teutobod : Historical Fiction by Kurt Hansen ➱ Join us for the Book Tour and Enter for a chance to win

Synopsis (from Amazon):

Daughters of Teutobod is a story of love triumphing over hate, of persistence in the face of domination, and of the strength of women in the face of adversity.

Gudrun is the stolen wife of Teutobod, the leader of the Teutons in Gaul in 102 BCE. Her story culminates in a historic battle with the Roman army.

Susanna is a German American farm wife in Pennsylvania whose husband, Karl, has strong affinity for the Nazi party in Germany. Susanna’s story revolves around raising her three daughters and one son as World War II unfolds.

Finally, Gretel is the infant child of Susanna, now seventy-nine years old and a professor of women’s studies, a US senator and Nobel laureate for her World Women’s Initiative. She is heading to France to represent the United States at the seventy-fifth anniversary of the liberation of southern France, at the commemoration site where her older brother, who was killed in action nearby, is buried. The site is very near the location where the Romans defeated the Teutons.

Excerpts

Excerpt #1

Chapter One

The smoke of the grist fires rose incessantly, grey black against the cloudy blue sky as the day meandered toward its middle hours. It was the season of harvest, and those konas who were able were out among the plantings, gleaning grain or digging turnips, carrots, or beets out of the black, loamy soil. Some ground grain into flour and some baked bread, while others tended the fires and the fleshpots. Still others were about the business of tanning hides, mostly of deer, raccoons, rabbits, or fox, occasionally from a bear. The smells of death intermingled with the breathing life and beating heart of the sveit.

Gudrun liked this time of day best. She grabbed another handful of golden wheatstalks, slicing off the grain heads with a strong whisking motion and dropping the grain into her tightly woven flaxen gathering bag. She paused for a moment, wiping the sweat from her brow with the back of her hand. The sun was bright today, making the air steamy. Gudrun looked out across the hills, down the valley, past the wooded glades where she could see dozens of other kǫngulls like her own, and she knew there were even more beyond the reach of her eyes. Most of the kǫngulls contained about 100 persons, but some had more. As she fixed her gaze closer, to the kǫngull where she lived, she could see the jungen, chasing one another, some wielding sticks or branches, others seeking to escape the assaults of their aggressors. The jungmädchen were variously helping their mothers with cooking or cleaning vegetables or sewing hides; the kinder simply hid in corners or clung to their mothers’ legs.

Several hours passed, and now the sun was receding, thankfully, because its blazing, yellow glare kept breaking through the billowing clouds all day, intensifying the laborers’ fatigue. Gudrun emptied her grain bag into the large, woven basket at the edge of the planting. The basket was filled to the brim, and as she plunged both hands into the basket, letting the harvested grain sift between her fingers, a smile of satisfaction softened her face. Filling up her basket all the way to the top was for her, a measure of the goodness of the day. She hoisted the heavy basket, glad for the leather strap she had fashioned to carry it. Before she designed the strap, two women were needed to carry the woven baskets—one on either side—especially when full. But Gudrun decided to cut a long strip from the edge of a tanned deer hide and, with a sharp bone needle she affixed the strap to her basket, allowing her to shoulder the entire weight by herself.

When she first showed her invention, one of the men—Torolf—chastised her for taking the piece of deer hide. He pushed her to the ground and threatened worse, but Teutobod intervened, bashing Torolf on the head with his club and sending him reeling. Teutobod, Gudrun’s mann, was the undisputed leader of their sveit, and he had been their leader long before he took her for his wife, ever since the sveit’s earliest days in Jutland. He ordered that all the grain baskets be fashioned with straps for carrying, and Gudrun won the admiration of all the konas (and even some men). Torolf avoided her from then on.

As evening approached, it was time to prepare for the return of the männer. Most hunting excursions were a one-day affair, bringing in meat for perhaps a few days at best. But as the harvest season proceeded, the männer would leave for days at a time, seeking to increase supplies for the long winter to come. This foray had lasted nearly a week, but Gudrun was told by Teutobod to expect their return before seven suns had passed, and she shared this information with the some of the other konas. By now all the kongulls were preparing for the männer coming home.

As the sun began to set, the konas started pulling out skins from their bærs, unfolding them and laying them on the ground about the fire pits. The flesh pots were stirred and stoked, and a hearty stew was prepared with deer meats, mushrooms, yellow beans, potatoes, turnips and carrots, seasoned with salt and fennel and black peppercorns. Flasks of beer that had been cooling in the stream all day were brought to each firepit and hung on a stake which had been plunged in the ground for that purpose. Various dinner ware made from carved bone or fashioned out of wood or clay were laid out. All was in readiness.

An aura of anticipation and anxiety tumbled around the kǫngull, shortening tempers as the waiting lengthened. Finally, about an hour after the sun had fully set, the sound of the ram’s horn distantly blasted out its announcement: Die männer komme! The jungen were hustled away to the kinderbærs. One never knew the mood that might accompany the hunters when they returned, and things could and often did get ugly. The konas sat or knelt respectfully beside the firepits, twitching, nervously swatting insects away from the food, inhaling excitement and breathing out fear.

Soon the rustling of leaves and the snap of twigs underfoot grew louder and closer until the shadows brought forth the whole troop of men, bustling in to the kǫngull, carrying or dragging the meat they had procured, pounding their chests, howling, pulling on their scraggly hair or beards, banging the ground with clubs or spears and smelling of the hunt and of the forest. Similar sounds of triumph and dominion could be heard resonating throughout all the kǫngulls below as the männer clamored in across the entire sveit.

Here in Gudrun’s kǫngull, the konas kept their gaze to the ground, their eyes fixed on the fire, and as the hunters’ swagger slowly abated, one by one the konas silently lifted their plates above their heads, each looking up to her mann as they all found their respective places. Once the providers were all reclining on skins beside the firepits, the konas stood and began to prepare plates of food for them. The men ate loudly, hungrily, slurping the stew from the lips of the bowls and using hunks of bread to grasp chunks of meat and vegetables.

The food having been consumed, skinflasks of beer soon followed, and before long the sated belches and grunts of the eaters gave way to boisterous banter, the proud providers reliving the thrill of killing a stag or the bravery of facing a bear. The konas scraped up the leftovers to take to the huts for themselves and the children, after which the cleanup tasks commenced. The women worked in groups of three or four, tending two large boiling pots to soak the dinnerware until all remnants of the food floated up to the top and were skimmed off. A little more soaking, then all the dinnerware was stacked and stored for the next use. Gudrun, along with two other konas, took the job of drying the cleaned dishes, swinging a dish in each hand to move the air. They playfully swung the wet plates or cups at one another, spritzing each other in the process and giggling like little meyas.

This being the end of a prolonged hunting venture, the children were tucked in early in the kinderhäusen, and the konas prepared to receive their husbands. For those unlucky enough to have brutish men, their wifely duties were not at all pleasant. Others were more fortunate. Gudrun was happy to be among the latter, hoping only that the beer ran out before Teutobod’s love lust. She retreated to the bær she shared with her husband, glad for the privacy his role as leader provided. This entire kǫngull was comprised of the sveit’s leadership and their skuldaliðs, and as such it claimed luxuries not generally known throughout the sveit by underlings. The leaders camped furthest upstream, and therefore got the cleanest water for drinking, cooking, and bathing. The leaders claimed individual space for themselves and their vifs, while others down below had to share living space with two or three other skuldaliðs.

Gudrun removed her garments and lay nude on the soft deerskins in her bær to prepare herself for her husband. Covering herself with another skin, she began to move her hands over her thighs and abdomen, softly, back and forth, her rough-skinned fingertips adapting to their more delicate uses. She moved a hand upward, swirling around her breasts and throat, teasing each nipple at the edges, holding back from contacting the most delicate flesh.

Her stroking and probing continued, a bit more urgently as she felt her breath rise and grow more heated. The muscles in her abdomen began to pulse, and as her hands found the sensitive spot between her legs, she felt the moisture beginning to flow inside her. When she was young Gudrun had learned from the older konas how to help her husband in this way, to ease his entrance and hasten his joy. Along the way, over the years, she also learned to enjoy herself more in the process. As the instinctive rocking motion in her pelvis began, she eased her manipulations, not wanting to be prematurely excited. Breathlessly, she looked toward the bær’s entrance, hoping Teutobod would hurry.

Excerpt #2

Morning snuck into the kǫngull like a soft-footed invader, its shafts of misty light meandering through the cracks and crannies of Teutobod’s hus and rousing him from his deep snoring. He saw that Gudrun was already awake, as expected. He knew that she and many of the other konas could be found standing in the river, washing off the sweat and smells of the prior day and night. Some of the men would be there as well, mostly those who had less tolerance for beer. It was common for männer and konas to share the river in the morning, though the groupings formed gender-specific circles that faced inward and kept a respectful distance one from the other.

Teutobod rose and headed down to the river to bathe. The aroma of beer brewing was pervasive. It was early, but the process of making beer was involved and took time. Those konas who brewed beer were called braufraus, maybe as a taunt originally, but the name stuck and became a title of some prestige over time. It was a highly valued and important position, a daily responsibility involving several steps. Their work began early, cooking the barley and soaking the bitter hops. After cooking down the grain, they mashed it into a paste, adding fresh water and hops and sealing the mixture in skin bags, which were then hung on bone hooks or wooden pegs on the walls of a brauhus. As the bags began to swell from the yeasts growing inside them, each was opened briefly to relieve the pressure. Occasionally, an old skin would give way under the expanding gasses, and the exploding Bang! could be heard everywhere, resulting in shrieks of startled laughter from the jungen. The yeasty, loamy smell of the brauhus wafting in the breeze was constant, like the rising smoke from the campfires. And like the demand for more beer from the men.

At the river, Teutobod found a group of his lieutenants and joined their circle. All the others feared and respected Teutobod, but he knew leadership was always subject to challenge. Teutobod trusted no one. That’s why his bone knife, razor sharp and stained with blood, was in its customary place, sheathed in a deerskin holster suspended from a sash around his midriff. Still, he knew from experience that while respect may be born out of fear, it is solidified in fair treatment. So, he took interest in the well-being of all the men of the sveit, and especially in the lives of those leaders and their skuldaliðs with whom he shared the close community of his kǫngull.

“You all had good reunion with your vifs last night?” Teutobod said with a lusty smile as he glanced around at the other men, temporarily interrupting their lathering and splashing. The nodding heads and smiling, bearded faces gave the answer. “You deserve it!” Teutobod said. “It was a good hunt!”

Torolf kept his gaze downward, saying nothing. “No success in your hus, Torolf?” Teutobod taunted him. Torolf was the one most likely to replace Teutobod as leader of the sveit, or at least to want to try. He was among the fiercest in battle and the most competitive in games of chance and hunting skill. His face was emotionless, his eyes focused on washing his loins as he responded, “My vif did not please me. I killed her. I’ll find another.”

The bathing stopped. All eyes in the circle of men were on Torolf, then on Teutobod. Torolf finally could no longer avoid the strong gaze of Teutobod, and he slowly met Teutobod’s blue eyes with his own steely stare. Everyone knew it was a man’s right to divest himself of a vif if she did not please him. But to kill her was not allowed, except perhaps in cases of adultery.

“What had she done deserving death?” Teutobod demanded. Torolf continued with the challenge of his eyes locked on Teutobod. “As I said, she did not please me.”

Teutobod had long known of Torolf’s penchant for aggression, especially towards women. He took his first vif, Sunga, during a raid on a tribe in the Moravian hills, and after the sveit got settled in that area, she regularly appeared bruised and bloodied, sometimes so much so that she was unable to do her work. The other konas had come to Gudrun to ask that she intervene with Teutobod on Sunga’s behalf, but Teutobod would not interfere in the affairs of another man’s hus. Sometime later Sunga bore Torolf a female child, and Torolf killed the baby in a rage, smashing its head on a rock and tossing it into the woods. Sunga was so horrified she stood in the midst of the kǫngull and slit her own throat with Torolf’s knife.

Torolf soon took a new vif from a raid on another, smaller tribe. Her name was Vilma, and for a time, he seemed to treat her with less violence. Luckily, Vilma had borne a son for him, and Torolf continued his generally benign treatment of her. What had happened last night to cause this sudden murderous behavior toward her, no one could surmise.

Teutobod responded, “Torolf, you are a strong warrior and a great hunter, but I think an evil spirit lives in you. I will have to decide which is more important. For now, you must bring Vilma’s body out to the place of preparation.” With that, Teutobod left the circle. All the rest of the men followed, leaving Torolf standing alone.

Excerpt #3

It was time for the washing again, a time made readily evident by the odors of sweat and barnyard emanating from the house’s bedrooms. “Phew!” Susanna said aloud as she deposited the variously strewn sources of her repugnance into the thatched laundry basket she balanced on her hip. The socks were the worst, she thought, holding back her breath as she tweezed a pair between thumb and fingertip that Karl had recently worn. She buried them under some less malodorous pieces. But a momentary sadness overtook her, and she stuck her hand back into the pile to feel those socks again. She recalled the lovely, clean smell of the strands of wool she had spun into yarn for the making of those socks, how the yarn slid through her fingers back then, how it spindled onto the spool, how the spool grew and grew, how she had shaped the cone of it. And she recalled her sense of connection to the sheep and to the land and to the later uses to which the yarn would be put. Handling the socks now, even soiled and disgusting, her fingers still remembered. She lingered, just for a moment, her bent back galvanized by the reverie.

Straightening herself, Susanna finished gathering the clothing as she moved from room to room. She headed to the new wringer washing machine Karl had procured for her after their fourth child was on the way. But looking through the curtains at the sunshine of this unseasonably warm late-May morning, she decided instead to head to the back yard and her old wash tub. “Let’s just do it the old-fashioned way,” she said to no one in particular, although Gretel cooed happily in response. Gretel, her youngest child now aged 8 months, smiled up at her mother from the confines of her makeshift playpen (a couple of planks hemmed in by two chairs against the kitchen wall). She was holding the little wooden rattle Oompa made her for at Juletide. Susanna smiled back at her and said, “Meine kleine Schatz, let’s go do our work outside today, shall we?” As if in anticipation, Gretel reached up for her mother and Susanna lifted her high in the air, eliciting a shriek of joy as she was guided down and whooshed right on top of the clothes in the basket. And out they went giggling to the back porch.

Susanna set the basket down in the grass and removed her daughter from the stinky-soft bed. Still grasping her rattle, Gretel happily sat in the cool, shaded greenness beneath the giant elm tree, one of seven which towered over the small farmhouse owned by the Neuenschwander family for three generations. Those seven trees engendered the name, Seven Elms Farm, which had identified the homestead to the residents of Schuylkill County for the last two of those three generations. Susanna pumped water for the washing and carried two large pails over from the well to dump into the washtub she had placed on the workbench Karl had built for just that purpose some years back. She added two capfuls of Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soap, agitating the water into a luxuriant foam. After retrieving her old washboard from its hanging hook on the back porch, she began the arduous task of civilizing her family’s rags.

Before Gretel, Susanna had borne two daughters and a son for her husband: Karla, Johann, and Marta, now aged 17, 16, and 11 years, respectively. Karla saw her name as a lifelong reminder of her father’s disappointment in her gender. Marta inherited the name of her maternal grandmother, and Gretel was named—at Karl’s insistence—after his mother (although in Susanna’s mind, it was after the Grimm’s fairy tale character). Johann, on achieving school age (and over his father’s objections), had quickly adopted the Americanized moniker, Johnny. His was a somewhat schizoid world, in that nobody at school ever called him anything but Johnny, and at home, he was always called Johann. He longed for the day his father would finally call him by his real name, but he doubted that day would ever come. One dare not cross Karl Neuenschwander on his family farm, especially when you are an only son who is of no particular use and who is not particularly interested in farming.

Of course, being disinterested did not excuse anyone from contributing to the ongoing work of the farm. All the Neuenschwander family members were required to do their part. Ten cows had to be milked morning and night, the barn had to be cleaned daily, and feed had to be distributed to the cows and to the calves and heifers, as well. The calves had to be bottle-fed until they were old enough to chew. There was a substantial chicken coop which needed cleaning at least every other day, and eggs had to be gathered and meal distributed each day. The pasture animals also needed tending. Sheep and hogs needed food and water. Eggs were taken to market weekly, and butchered pullets monthly. Fences had to be regularly inspected and sometimes refashioned.

It was a year-round, non-stop cycle of working. In the spring, rocks pushed up by the melting permafrost had to be picked up out of the fields to prevent damaging the implements used for plowing and planting. In the harvest time the wheat had to be shocked, the corn picked and stored, and the fields prepared for the fallow months. And in Winter, all the livestock work continued without a break, much of it rendered more difficult and time-consuming by the rages of ice and snow. And then, of course, there was the rest of the work to do. Like the gardening. And the canning. And the meal preparation and cleanup. And the mending. And . . . the laundry. Always more laundry.

Susanna finished wringing out the last of the now clean clothing and set about the task of hanging it on the clotheslines. She looked down to see little Gretel, busily inspecting the grass and twigs near her spot in the yard. She had a furrow in her little brow, inspecting each leaf or pebble as though solving a complex puzzle. Susanna smiled at the scene. So serious! And so curious! It made her wonder if Gretel would keep this intense curiosity, and what the future might hold for her if she did. No use worrying about that, she mused, and she turned back to the task at hand. One piece at a time, shaken out, hung up and pinned to the line. One at a time. Do your work, and all will be well. That’s what her mother used to tell her.

She moved her way down the line, away from the house and toward the edge of the cornfield, then back toward the house with the next clothesline. She couldn’t see Gretel for a few minutes, and when the last piece of laundry had been hung up, she grabbed up her basket and headed back, ducking and weaving through the maze of wet clothing along the way. There was Gretel, slumped over and snoozing in the grass. “Meine kleine Engel,” Susanna whispered with a smile. She lay down beside her, carefully, and watched her breathing. Not a care in the world, she thought to herself. She began again to think about Gretel’s future, and before long mother and daughter were softly soaring together, winging above the toil and worry, adrift on the dreams of a summer morning.

Excerpt #4

It was Saturday and the Neuenschwander women were out tending the garden. Karla leaned on her hoe and looked at the sun’s position in the early afternoon sky. “Mutti, I hate to leave you while there is so much to do, but I have to get ready for my lesson with Professor Schutte.” Karla had been nurturing a natural talent for music since she was a child. Her mother saw her giftedness early and encouraged her. Over the years Karla began to sing often for her family, especially during winter evenings or on long rainy days. Her father first disparaged the idea of lessons, calling it an extravagance; but after she learned to sing Schubert lieder and then an aria from Wagner, he stopped complaining. Once, after Sunday dinner, he even requested a song from her. That was a proud memory for Karla.

“No, no, meine Süsse, I’m glad for you to go,” Susanna responded. “Your voice is a gift to the world from God, and you must nurture it.” Karla responded to her mother’s praise with a smile and a brief embrace before heading to the house. What her mother did not know was that Karla was just as interested in nurturing her relationship with Hans Schutte as she was in nurturing her voice. It was Hans she was thinking of as she headed to the washroom to clean up. She splashed her face and arranged her hair in an attractive bun. She looked at her face in the mirror, considering her eyes, her cheeks, her lips, trying to imagine her face from his perspective, wanting to be attractive to him. This was a brand-new affectation for Karla, and it was exhilarating and not a little daunting.

Heading out to the farmyard, Karla thought about asking her father for permission to use his truck, but decided against it, opting instead to ride her bike for the two-mile trip into Shenandoah. She disliked the image of riding a bike like a girl when she wanted so badly to be regarded as a woman, but the prospect of a confrontation with her father made the bike ride somehow less repulsive.

She headed down the end drive to the road. The image issue aside, Karla truly was an outdoors person and loved every minute of the trip. All of nature seemed to her to be fairly crying out for connection. She noticed the smell of hay and fresh manure perfuming her senses. It was for Karla the smell of growing, of life. A cardinal sang out a whistling overture and its mate responded. Tree frogs were sending out their raucous signals, each to another. Crickets and grasshoppers were similarly engaged in the musical back and forth of seeking mates. And along the way into town, Karla was warming up her voice, too.

As she approached the Schutte home, the size of the place impressed her yet again. It was a very old Victorian structure with an immense front door—at least ten feet tall with a dormer window above—and an old bell pull which, amazingly, still functioned. This was the home of Hans’ mother, Hannah, the widow of the Rev. Dr. Adolf Schutte, a local Methodist pastor who had died of cancer 18 months ago. Hans’ father had been deeply loved by his congregation, and after he died, the elders voted to allow Hannah to remain in the manse for as long as she wished. Hans had just received his position as assistant professor at Albright College in Reading that same year, so he adopted the routine of coming home weekly to look after his mother; he taught a few private voice and piano students while in town.

Karla pulled up to the yard of the Schutte house and quickly discarded her bike outside the bushes that lined the fencerow. She straightened her dress and patted her cheeks on the way up the front porch stairs. She pulled the antique doorbell just as Professor Hans Schutte was opening the door.

“Come in, come in,” he said, “it’s so nice to see you again! I want to hear your lovely voice. Come in!” He stood to the side, ingratiating himself a bit and motioning her in with his left hand, ever the gentleman. His right hand found its way to the middle of her back to guide her gently to the parlor. Karla felt an electric shock shoot up her spine at his touch. She hoped she wasn’t blushing.

“So how is the voice today?” the professor asked as he sat down at the Baldwin baby grand piano. “Let me hear, gently at first. We don’t want to damage the instrument. Let’s start with a nice, round ah,” he said, as he pounded out an E major chord. The sound of the chord brought an automatic response from Karla, and she sang out a perfectly rounded “ah” to the first five notes of the scale, holding the fifth tone for two beats before descending once again. Do re mi fa soool, fa mi re do. “Good!” came the professor’s response as he moved up one half-step to F major, with Karla following. As the routine of warming up continued, higher and higher and then back down again by half-steps, Karla could feel her throat muscles beginning to relax and the vibrancy and resonance of her tone became more obvious and natural. She was glad for the music and its focus away from the professor’s strong shoulders. “Now,” the professor said, “you are all warmed up, yes?” Karla thought to herself, “If you only knew,” but she simply responded, “Yes, Professor Schutte.” He said, “Very good. Now sing the Schubert Nacht und Träume for me.” There was nothing she wanted to do more.

Excerpt #5

It was the tenth day of August, and the Avenue Gabriel was lush and steamy with the heat of the French summer. The full, green trees lining the grounds of the U.S. Embassy provided shade but no relief from the sauna-like conditions imposed by a 26℃ dewpoint. Graduate student Cecilia Drexel pulled a hankie from her backpack and wiped the sweat beads from her forehead as she arrived at the gate.

“Bon jour,” she said to the Marine who guarded the entrance.

“Ma’am. What is your business at the embassy today?” he asked.

“I am here for an appointment with Ambassador Eberhart.”

“I need to see your passport and identification,” he said, matter-of-factly. Cecilia tossed aside a sweaty strand of unruly, brown hair and dug out the necessary papers. The guard examined her identification, looking back and forth between her and her ID photo.

“I need to search your belongings and your person,” he said. She handed over her backpack and waited while he examined its contents. “Raise your arms please, remove your footwear, and stand spread-eagle, facing me,” he said, and she stepped out of her worn leather flats and spread out. He ran a metal detection wand closely up and down, in and out. “I am sorry for being intrusive, but I must pat you down. If you prefer, I can call for a female Marine.” Cecelia said, “No matter. It’s the way of the world now, I guess.”

“Yes, ma’am,” the young man replied. “Please turn away from me and remain in a spread-eagle position.” Cecelia complied with his direction. He felt all around her armpits, her breasts and the edges of her brassiere, her sides, the waistband of her slacks, and down the inseams of her legs. He thoroughly examined her shoes before returning them. “You can put these back on now,” he said, “and again, I’m sorry for the intrusion. But as you said, it is the way of the world right now.” He stepped over to a small guardhouse and pulled out his daily log. “What time is your appointment with the Ambassador,” he asked.

“It is scheduled for 2pm,” she said. “I am a bit early.”

“No problem, ma’am,” he said, softening a bit now that he had established her identity and reason for being there. He spoke briefly into a shoulder-mounted mic and received a response. “The Ambassador’s aide will be here shortly to escort you.” He pointed to a stone bench in the nearby shade, “You may sit here while you wait if you wish.”

Cecelia sat down, again pulling out her hankie to clear the moisture from her forehead and eyes. “Is it always this hot here?” she asked the guard. “You must be very uncomfortable in that uniform.”

“It has been unusually warm,” he said. “You get used to it.”

A thin, obsequious-looking young man wearing a tailored suit soon appeared at the gate. “Miss Drexel?”

She looked up. The suit looked maybe one size too large for him. She stood and said, “Cecelia is fine. Yes?”

“Thank you, Cecelia. I am Michel Bertrand, aide to Ambassador Eberhard.” His thick, French accent was apparent. “Welcome to the American Embassy,” he said. “If you would please follow me.”

They walked through the gate and entered through two enormous iron doors into the interior of the impressively columned edifice which housed the Ambassador’s offices. It was hard not to be impressed by the structure itself. Cecelia noticed feeling a sense of safety and strength oozing from every direction, beginning with the statue of Benjamin Franklin in the entry garden.

Her guide began reeling off what seemed to be a canned travelogue. “You will find that history is displayed everywhere you look. Here is the famous “witch” mirror in the foyer, dating back to the American Revolution, so nicknamed because of the distorted image its convex surface produces. And these two marble columns in the entryway display sculptures of two great warriors of your country’s revolution, General George Washington and the Frenchman Marquis de LaFayette. Both busts were created by Bartholdy, who designed the Statue of Liberty. The large portraits on this wall are of the Comte de Rochambeau and the Marquis de Lafayette.”

Looking up, Cecelia could see a grand stairway flanked by ornate balustrades leading to the second floor. “As you can see,” the aide’s travelogue continued, “hanging on the walls of the staircase are two oil paintings by Gilbert Stuart, the larger is of course George Washington and the lesser is James Monroe, who was the first minister to France from the new republic. You may have also noticed the image of the American eagle, which can be seen in the woodwork, in brass finials, in paintings and sculptures, and in the Great Seal of the U.S.A. everywhere.” Cecelia sensed a bit of derisiveness in the way he emphasized the word, ‘everywhere’.

They passed under the staircase to a beautiful atrium area, gracefully appointed with eight magnificent chandeliers. “Here is the Wallace library,” the aide motioned, which contains many historical volumes from both our countries dating back to Revolutionary times.” He motioned for Cecelia to be seated, and he said, “I will inform the Ambassador of your arrival.”

Cecelia sat and considered her surroundings. “The things that have gone on in this place!” she thought to herself. She considered the intrinsic link between the US and its oldest ally, and the immense role that link had played in world events. “Two world wars, the interaction in French Indochina, the partnership in dealing with terrorism . . .” Her musings were interrupted by the return of her guide. “Cecelia, the Ambassador will see you now.”

Cecelia was led into a beautifully appointed office of grand dimensions, with a large, antique-looking desk at one end. Behind the desk was a wall of windows looking out across the Place de la Concorde with its many statues and fountains stretching out beyond the Champs Elysees. Framed by this glorious view of Paris stood the person Cecelia had been waiting to meet, the U.S. Ambassador to France. “Ms. Drexel, please come in and make yourself at home. This is your home, in true terms; you are standing on American soil here. But I suppose you know that.”

“Madame Ambassador, I am so very glad to finally meet you. Thank you for agreeing to meet with me and for considering my proposal. And please, call me Cecelia.”

The Ambassador moved from behind her desk and joined her visitor in a seating area across the room. “It is my namesake you should thank. She is the one who set this up.” She took Cecelia’s hand and grasped it warmly before she sank into a sumptuous brown leather chair and crossed her legs. “And you, Cecelia, if you truly intend to write my grandmother’s life’s story for your dissertation, you had better call me Gretel.”

You never know where researching a book might take you! While researching the WWII portion of Daughters of Teutobod, I learned about the earliest training of the Army Rangers. After gathering at Carrickfergus in Northern Ireland, the group headed off to the highlands of Scotland for intensive combat training, after which they returned to Carrickfergus to await deployment. A fascinating sidenote for me related to the treatment of Black soldiers, many of whom related how wonderfully they were treated by the Irish people. They were welcomed into homes and pubs and treated as equals among their lighter-skinned compatriots. When some of the White soldiers complained to their commanding officers, the officers addressed the "morale" problem by attempting to force local business owners to impose race restrictions on the soldiers they served. The locals would have none of it! They all stood up to the American officers and reminded them they were guests in Ireland, and that they (pub and restaurant owners, mostly) would not be told whom they could serve in their own country!

For me, the experience of the Black soldiers intersects with the experiences of women in history. Being called to serve (for women, in roles such as mother, wife, nurse, schoolteacher, etc., and for Blacks in roles of servant or even soldier) has come with a tacit exclusion from full participation in the world of those they served. The message has been, “be a good little (fill in the blank), but don’t bother the men. You don’t really belong here.”

AUTHOR INTERVIEW

Author Bio:

Kurt Hansen is from Racine, Wisconsin, and has lived in Kansas, Texas, and Iowa. He has experience in mental health and family systems as well as in parish ministry and administration. He holds degrees in psychology, social work and divinity. Kurt now lives in Dubuque, Iowa with his wife of 44 years, Dr. Susan Hansen, a professor emerita of international business. Kurt is the author of Gathered (2019). Daughters of Teutobod is his second novel.

Website: https://www.authorkurthansen.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/revkurthansen

Author Marketing Experts tags for social media:

Twitter: @Bookgal

Instagram: @therealbookgal

Amazon: https://amzn.to/3LqVS8A

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/62795806-daughters-of-teutobod

GIVEAWAY

Join us on the #BookTour with Guest Post & #Giveaway

#daughtersofteutobod #historical #familylife #fiction #kurthansen

Hosted by ➱ Author Marketing Experts

Comments

Post a Comment