“Where is your focus, nephew?” My uncle demanded.

I turned from surveying the gardens spread out behind the palace. “The kings of Salar,” I began again, reciting my lesson from memory despite my longing to be outside in the greenery. I might only be twelve, but I was a prince. The title came with responsibilities.

“In Caragh, boy,” my uncle demanded. “Or if you must, that dialect they speak in Salar or one of those other two countries near there.”

“Mairead and Edan,” I offered.

“What?” he grimaced at me as he rubbed his leg absentmindedly. Soon he would begin stomping about to relieve the pain and stiffness of his old injury.

“The two other countries who share the same primary language with and neighbor Salar are Mairead and Edan,” I kept my tone respectful despite his sharpness.

“I didn’t ask for that information.” He groaned. “Why can’t you just stick to what I requested? Recite your lesson about the kings of Salar in their dialect and then in the language of Caragh. I will see that you master these languages before I die.” He grabbed his cane and hauled himself from his chair.

I immediately launched into the memorized speech. Then, I spent the next hour reciting the history of one of the obscure kings who reigned only a few decades past.

Meanwhile, my uncle, Mirza Darush, lumbered about the portico with his stick, tapping the tiles at a regular rhythm.

This was my life: memorization, recitation, and repetition every day. My uncle loved making lectures on my new levitated status in life and how it was now my duty to make the family proud. Unlike my mother, who elevated herself by marriage, I must maintain our status with my hard work and skill as a future ambassador. Languages, culture, finance, and endless speeches, I needed these skills. However, all I wished to do as I studied was escape.

My eyes strayed of their own volition toward the gardens. A young voice, feminine and clear, rose in a lilting playful song with a beautiful tone. I couldn’t see the singer, but I envied her. She was outside in the clear air beneath the shade trees.

“Continue, Cyrus,” uncle demanded.

“Pray, uncle, what is that singing?” I asked.

“Mmm?” He lifted his shaggy, graying head and narrowed his eyes in concentration.

“Is it a servant? She is singing in an obscure Salar dialect.” Her pronunciation was precisely what my language master had demonstrated.

“She is indeed.” My uncle’s eyes widened with sudden amusement.

“A servant?” I didn’t know he employed foreign servants.

“No, she is singing in a dialect. Probably her native tongue.” His dark eyes studied my face for a moment. “Perhaps it is time for a break. Go, run, and play.” He waved toward the garden. “We are finished for the day.”

I didn’t wait long enough for him to change his mind. Not bothering with the path, I took off across the tiles at a run, hurdled a hedge, and landed on the soft grass beyond with a whoop. Darting down the slow decline toward the bottom of the garden, I headed to where the deep green foliage took on a wild look. It grew against the great wall surrounding my uncle’s property in the center of the capital of Kamendu.

Once out of sight of the palace, I followed the voice as it sang about dancing.

The sound grew louder as I approached my favorite thinking place. The corner of the garden where a giant tree arched over the wall, completely shading the corner of the lawn, keeping it cool and still even on the hottest day of summer. This was where I found the singer, a dark-haired girl with a pale complexion and wide, startlingly green eyes.

“I didn’t break anything, I promise,” she immediately declared in my language. “I will go the way I came. Please don’t tell anyone I was here.” With that, she grabbed her skirts so that I could see the bottoms of her loose trousers as though she was preparing to run.

“No, wait,” I commanded. “How did you get here?”

To my utter surprise, she obeyed. Dropping her skirts, she folded her hands at her waist, lowered her head demurely, and offered me a deep bow. “My apologies. I entered through the wall. The door along there was unlocked when I tried it a few weeks ago. No one comes down into this corner, and I….” Her voice tapered off as she glanced up at me without lifting her head completely. “You aren’t angry, are you?”

“No,” I admitted. Her accent was adorable.

“Then why are you glaring?”

“I am not glaring.” Despite my denial, I could feel my brows drawing together. It took effort to ease the tension between them.

She smiled, tilting her head to the side like a little bird or the puppies in the stables. “You look better now. More welcoming.” She alternated sides, causing her hair to escape from her loosening scarf. A thick loop of dark, glossy hair draped one side of her face.

“How old are you?” I asked.

“Eight. You?”

“Twelve.”

“You look older than twelve when you aren’t frowning.”

“And when I do?” I asked, purposefully lowering my brows and exaggerating my down-turned mouth.

She laughed. A bright warm sound that burst through the quiet magic of our haven in as her singing had. She sounded like joy, happiness, and all the things I missed about being near my mother. I hadn’t heard anyone laugh in so long. A jolt of longing shot through me.

“Oh, no, now you look like you are going to cry.” She sprang across the space between us and wrapped her small hands around my arm, well-muscled from saber drills and working with horses. Her hands were tiny in comparison. She plead up at me, “Please don’t cry. I don’t know what I did to upset you, but I am sorry. Please don’t cry.”

I blinked away the sting behind my eyes. “Men don’t cry.”

She stepped back and planted her fisted hands on her narrow hips. “Men do too cry. My father is a man, and he cries. He cries when Mother gets worse. He cries when it looks like she is going to die. Men cry.”

The sheer conviction of her declaration struck me. When was the last time anyone other than my uncle had talked to me that way? I couldn’t recall.

“What is your name?”

“I am not allowed to say.”

“Why?”

“I have to go.” She gathered up her skirts again. “You should probably go too. Your master is going to be looking for you.”

“But I don’t know your name.” I was loath to let her go without some connection that I could use to find her again. “Can you come back here tomorrow?”

She took a few steps toward the hidden door before hesitating. She glanced over her shoulder at me.

“Please. My name is Cyrus. There I have given you my name. Can I have yours now?”

She turned half toward me, half toward her escape route. She studied my face as she worried her bottom lip between her small, white teeth.

“I promise to not tell anyone,” I offered.

“I have to go,” she turned away again.

I tried one more time. “Please,” I called after her, resisting the temptation to follow her. It would be foolish to do so. It would probably make her feel less safe, thus less likely to return. Oh, how I hoped she would return.

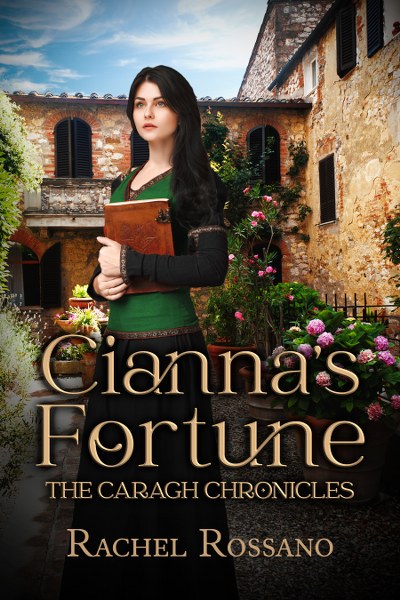

“Cianna,” she called over her shoulder.

“Then same time tomorrow, Cianna.”

She didn’t respond as she disappeared beneath the branches of the massive lilac bush blocking the hidden door. However, I was already forming a plan, an excuse to make sure I could linger in the garden in time to meet her. I would simply tell my uncle that I needed to practice my conversational Caragh. What better way to do that than with a native? Even better, a native my age.

I walked back toward the palace as I worked over the actions I could take should she not appear. At least I had her name now. How many Ciannas could there be in Kamendu? I doubted there were any. It was such a clearly Salarian name.

Comments

Post a Comment